Patriarchy as a ubiquitous contextual reality has impacted how technology interacts with different genders. Gender and sex as differentiated by feminists as social constructivism and biological determinism respectively– gender is comprehended is how one is raised and conditioned. Women as agents of domestic realm and men as agents of public realm is how we can understand normative framework of gender. The dichotomy between sexes is created in our internalisations of how women and men are supposed to be in different settings. This understanding percolates in the manner men and women interact with and access technology. The advancement of science and technology resulted in several revolutions especially changing the ways in which we interact with each other. However, the larger sociological process that influences our daily behaviours and accessibility of different resources are manifestations of patriarchy. It is patriarchy in India when mobile phones are considered provocative instruments for rape incidents and sexual harassment. It is true that technology doesn’t discriminate between genders, however, design of technology is based on heteronormative matrix. The genders are perceived in their social contexts which are determined by our social conditioning. Based on these tenets, gender gap in the digital space is equally universal and must be addressed in order to create a more inclusive, gender equal space.

Empirical Evidence

Various research studies have suggested that digital divide has emerged along the lines of previously existing social divides. The divide between genders is a reproduction of social inequalities existing in our societies and political settings. The gaps further determine how technology provide opportunities to access information, a necessary tool for participating in a democratic context. Research has indicated that women lag behind men in the ownership of technology and the utilization of technological expertise. Anthony Giddens, a sociologist, argues that differences in access to any kind of resources is dependent on structures of the society. The structuration theory establishes a connection between individual’s desires, social structures influencing their behaviours and the way they think about objects as technology. There are two kinds of access determining the gender digital divide. Firstly, cognitive access comprising of individual resources like attitudes, anxiety and skills for accessing technology. Secondly, social access refers to cultural norms and social resources embodied in different social groups. In case of gender divide, both the kinds cognitive and social norms have impeded the access to technology. Research evidences in USA and European countries have revealed that boys indicated more positive attitude about computer technology than girls. This research conducted by Gita Wilder, Diane Mackie and J. Cooper have contended that these differences in attitudes towards computers and internet becomes quite ostensible in the fifth grade and even furthers through the middle school and high school years. Similarly, other empirical evidences by Cooper and Weaver have suggested that women would often avoid taking up course relying on technology in their university education. Women in such cases didn’t lack technical skills as on the contrary same researchers have revealed that four out of five women had completed courses in calculus. Cooper in his research borrows from Reinen and Plomp (1997), ‘concern about gender equity is right.. ‘concern about gender equity is right. . . Females know less about information technology, enjoy using the computer less than male students and perceive more problems with. . . activities carried out with computers in schools’ (Cooper, 322).

The structuration theory points out the role of institutions and structures in providing access to technology. The social practice of public access to computers and the internet has elements of structure: institutions which have library system, community centres, or others decide to put in public access computers. Giddens here draws a correlation between individual’s agency (possibility of individual action) and structures of social setting arguing that structure is both enabling and restraining. This can be further understood in consonance with social construction theory envisaging that technology is socially shaped according to different social contexts, the way society is structured informs the technology shapes, designs and meanings. Social construction theory argues that potential media ultimately produces messages that are suitable for a given society. It is true that in this manner technology opens up new possibilities for genders as how different gender roles might be performed in new areas. And in the social setting, gender shapes the construction and meanings of technology. This becomes visible in the way gender gap closes in the 1990s when it comes to possession of ICTs. The empirical evidence post 1990s has unveiled that gender gap in skills and usage remains, however, these gaps are far more prevalent among adults. Similarly, Pew National Surveys of computer/internet point out that visible gender gap in overall computer or internet use in the late 1990s disappeared by the 2000s. However, at institutional level such as libraries, public centres such gaps continue to be determined by gender inequalities and accessibility.

Gender gap in the times of Internet and AI

This report at Livemint argues that patriarchy remains the underlying phenomenon for unequal access to technology among genders. Quoting a UNESCO report, Sahil Kini has pointed out that 70 percent of internet users are men. According to the world data of 3.58 billion internet users, “2 billion (56%) are men and 1.57 billion (44%) are women. Of that shortfall of 430 million users, 42% comes from India”.

In terms of owning a mobile phone, an Indian Express report reveals that there exist a stark contrast between genders. According to the study conducted by LIRNEAsia, an information and communications technology (ICT) policy think tank based in Colombo, “only 43 per cent of women in India own mobile phones compared to almost 80 per cent of Indian males — mostly because of a lack of awareness”. The gender gap in rural areas in 54 percent whereas in urban areas it is 34 percent.

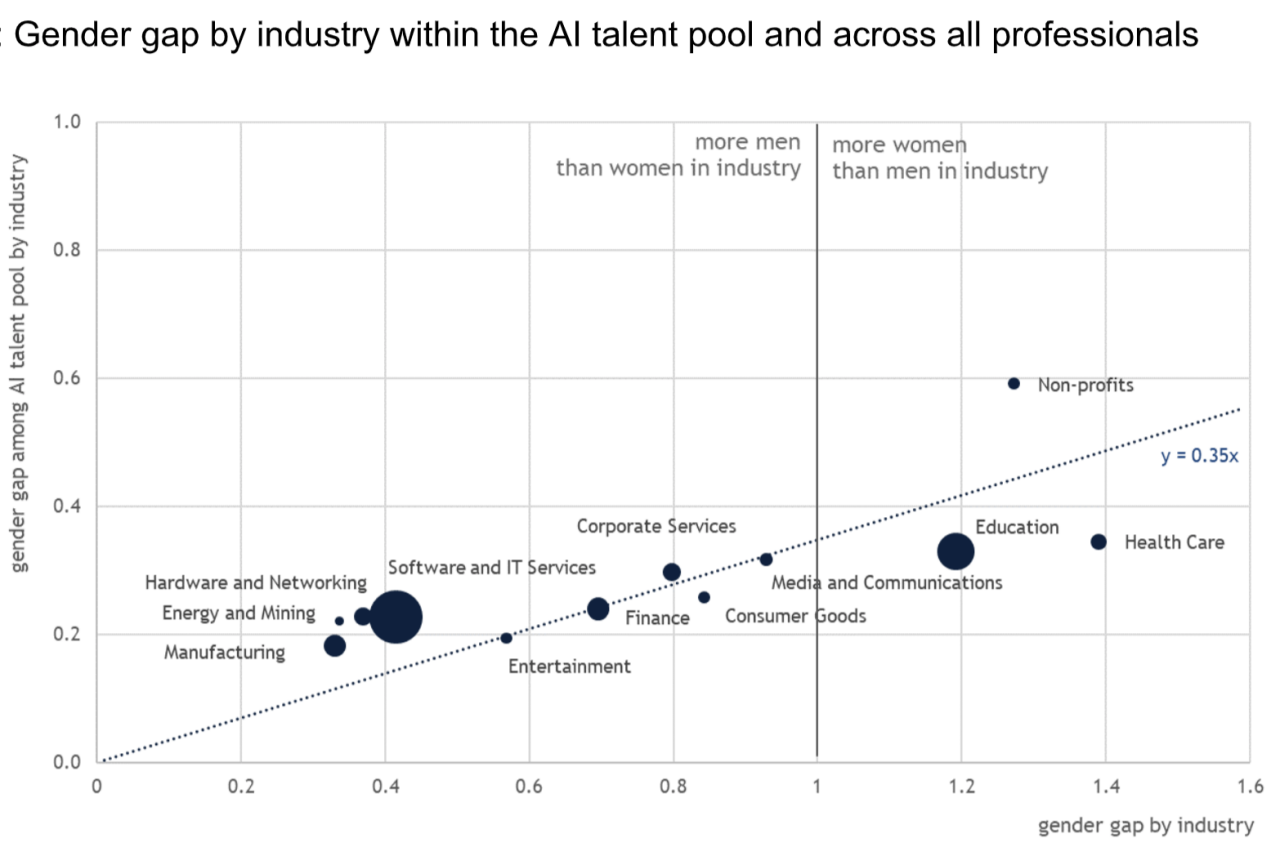

In the field of artificial intelligence, Global Gender Gap report 2018 produced by World Economic Forum (WEF) in collaboration with LinkedIn has pointed out that only 22 percent are women are represented in the workforce. Women are generally employed in the positions of data analysts, researchers, information managers and teachers. Women in AI are only more represented in lower paying industries like non-profits, education and healthcare. As reported in CNBC, “The analysis found that the AI gender gap is three times larger than other industry talent pools”.

Another report at Quartz, has argued that women students in artificial intelligence are severely underrepresented. The report argues, “Less than 20% of faculty at top universities are women, according to the AI Index data, which looked at seven top universities in the United States and Europe”. Further, the percentage of women seeking jobs in AI in USA is 29% as compared to 70% men.

The research in AI already remains male-centric. In 2017, the researchers at the universities of Virginia and Washington showed that the image collections and algorithms deployed in teaching AI involve examples that portray the same societal conditioning of genders. For instance, women are related with activities in domestic realm like washing, cleaning etc. Another depressing scenario that has been reported is in the field of machine learning where women are significantly lesser than men. The pie chart below speaks volumes on this.

Source: Percent of men and women who contributed work to three leading machine learning conferences in 2017. Source: Element AI

Source:https://in.finance.yahoo.com/news/women-already-losing-war-robots-taking-jobs-230105183.html

Similarly, the automation of certain jobs has disproportionately affected women impacting their traditional jobs. At the same time, women remain underrepresented in the fields of Science and Technology, Engineering and mathematics (STEM). The report’s author’s have argued that, “the possible emergence of new gender gaps in advanced technologies, such as the risks associated with emerging gender gaps in Artificial Intelligence-related skills”. It is imperative to understand that gender parity is essential in emerging nations for both the booming of economy and polity.

“Saadia Zahidi, head of the Centre for the New Economy and Society and member of the managing board at World Economic Forum”, in this report said industries must ‘proactively hardwire gender parity in the future through effective training, reskilling, and upskilling interventions and tangible job transition pathways’.

The gender inequality in technological and digital space is largely a manifestation of the happenings in social worlds. The answer to all these gaps and persistent chasms is to first address the source of why girls at a young age are ‘supposedly’ disinterested in technology. The differentiation of this world into pinks for girls and blues for boys, beauty for girls and technical for boys has continued to set a benchmark for various skill-sets and resources. The solution to these dipping percentages lies in addressing the discrimination that exists at the level of upbringing. The social settings and frameworks need to be more engendered so that boundaries between pinks and blues are not stringent and porous to cross-over.